Knowing the Unknown Soldier

An Open Letter to my Hometown of Floyd Virginia

By Mara Robbins

There were a lot of things I didn’t know before recent years brought racist flags out of people’s yards and basements and onto the streets of my hometown, and after the terrible shooting in Charleston where nine black people in a bible study group were murdered by Dylan Roof. There were a lot of things I didn’t know before witnessing riot gear on the streets of my hometown when there was a “rally and ride for confederate pride” in early September while we still grieved the tragedy in Charlottesville. There were a lot of things I didn’t know before the death of George Floyd brought the realities of racism in America undeniably before the eyes of conscientious people everywhere.

There were a lot of things I didn’t know before recent years brought racist flags out of people’s yards and basements and onto the streets of my hometown, and after the terrible shooting in Charleston where nine black people in a bible study group were murdered by Dylan Roof. There were a lot of things I didn’t know before witnessing riot gear on the streets of my hometown when there was a “rally and ride for confederate pride” in early September while we still grieved the tragedy in Charlottesville. There were a lot of things I didn’t know before the death of George Floyd brought the realities of racism in America undeniably before the eyes of conscientious people everywhere.

Yet once I know? I cannot UN-know.

There are a lot of things I didn’t know then and a lot of things I won’t share now because those who share them with me do so in trust that I won’t risk their safety

by revealing them. As someone who has been targeted by fascism in America due to my outspoken public presence, I know what it feels like to be terrorized by racists, white supremacists and petro-colonizers. Many stories that are shared with me have to be held in trust because those who tell them fear repercussions. I care deeply about harm reduction. I do not want to put anyone at further risk. One of the ways I utilize my privilege as a middle aged white woman is to be entirely public with my own voice, opinions and images, sometimes being graced with the trust to represent others anonymously with their informed consent.

Please take a moment to deeply consider what this means. Based on continued harassment, threats and violence from white supremacist groups? It is dangerous to make your anti-racist views known. This is true for anyone, though it is, of course, much more of a risk if you are black. Many have asserted that it should be the black community who decides what should happen to the statue on Floyd’s courthouse lawn. Though this is well intended, and I do encourage anyone who is white and wants to be an ally to follow the lead of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) organizers, please consider that Floyd is only an hour away from Martinsville. The Southern Poverty Law Center has confirmed a group of Rebel Brigade Knights True Invisible Empire, a branch of the Ku Klux Klan, in that city. Because of unfortunate events in Floyd that have glorified the racist flag and the confederate monument, groups such as the KKK pay more attention to what goes on, therefore creating more risk for those who are most vulnerable. It is not realistic, wise or safe to place that kind of weight on the shoulders of the black community of Floyd to publicly decide about what happens to that statue. It is up to those of us who are white (most of our population base–over 96% last time I checked) to refuse to stay silent and perpetuate the continued presence of violent symbols to contradict the peaceful nature of our town and county. It is up to those of us who are white to recognize our privilege, challenge our fragility and stand up and say NO to hate speech, hate groups and symbols of hate, terror and racism. Many of us might defend ourselves by saying “but I am not racist.” That is not the same as being anti-racist. In order to keep racism from being passively allowed a presence while claiming to protect “free speech” we have to redetermine what it means to feel threatened by symbols and speech. Our community has been, and continues to be, threatened by racism.

And once we know? We cannot UN-know.

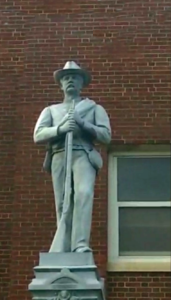

Growing up, I heard the confederate statue referred to as the “Unknown Soldier,” though according to the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, it is called the “Courthouse Common Soldier.” This center, located at Virginia Tech, also indicates that the “tribute is interesting for its reference to the county’s confederate dead as “our fallen braves.” The implicit comparison of confederate soldiers to Native American warriors is perhaps designed to lend the boys of 1861-1865 an air of nobility and courage tempered by the futility of their cause.”

Dear Floyd, has anyone asked any local indigenous communities how they feel about the term “braves” being used in a tribute on a confederate monument? I feel that would be a respectful thing to do. I would also hold their opinions in confidence unless given explicit consent. Again, the risk of repercussions is great.

Given that the population of Floyd is predominantly white, it’s important to acknowledge that when white people allow symbols and representations of slavery, colonization and other cruel portions of our history to continue a legacy of violence, intimidation and oppression that we are complicit in their continuation. Passively allowing a confederate monument to be centered at our courthouse is an example of something I hear often right now: “white silence is white violence.”

The statues delivered by the Daughters of the Confederacy to communities across the south were intended to be a threatening presence. They towered over our better selves and better intentions, threatening the black community and others when a physical presence of authority (such as a police officer) was not present. They promote, perpetuate and emphasize white supremacy. If you have lingering doubts? According to the publication Facing South: “Sixty-one years after the end of the Civil War, the UDC constructed a memorial to the Ku Klux Klan outside of the city of Concord, North Carolina.”

And yet over and over again, there are some in Floyd who present their own experience of the monument and the racist flag as facts. I do not deny people their personal truths or favorite stories, often passed down through families and often overlooking racism altogether, even if I disagree. There are still some in Floyd who strongly disagree with the facts. But disagreement does not equate accuracy. By all means, this narrative must be challenged.

Our actual history and heritage in Floyd County is nuanced and complex. It deserves to be honored through celebration of diversity, inclusion and compassion. What we inherit from our ancestry, though it is part of our heritage, can also be laden with trauma and maladaptive habits. Do we choose to look the other way when faced with the uncomfortable realities of our own racism? Or do we work together as friends and neighbors to learn, grow and prosper as families and beloved community? Simply knowing that we have white privilege is not enough. We must be willing to leverage that privilege to help create justice for everyone.

Because once you know? You cannot UN-know.

Removing the unknown soldier from the courthouse lawn will make many things known. It will be made known that the citizens of Floyd County no longer tolerate symbols of racism. It will be made known that we will not be bullied and abused into silence by the presence of white supremacy in our community or our government. And it will facilitate previously unknown stories to make their way from the shadows of our dark past into the light where healing can begin.

Knowing what we now know, it is evident that the unknown common soldier does not represent the Floyd we all know and love. Local leaders must take swift action to immediately remove this racist monument from our public ground. I fervently hope that those who disagree with this action find compassion in their hearts for those who have been brutalized by racism and choose to change their minds. I hope they do not create another “lost cause” battle of division and unnecessary separation. I hope they are able to understand that in order to preserve the peace, the statue must be removed. It is time. #TakeItDown.